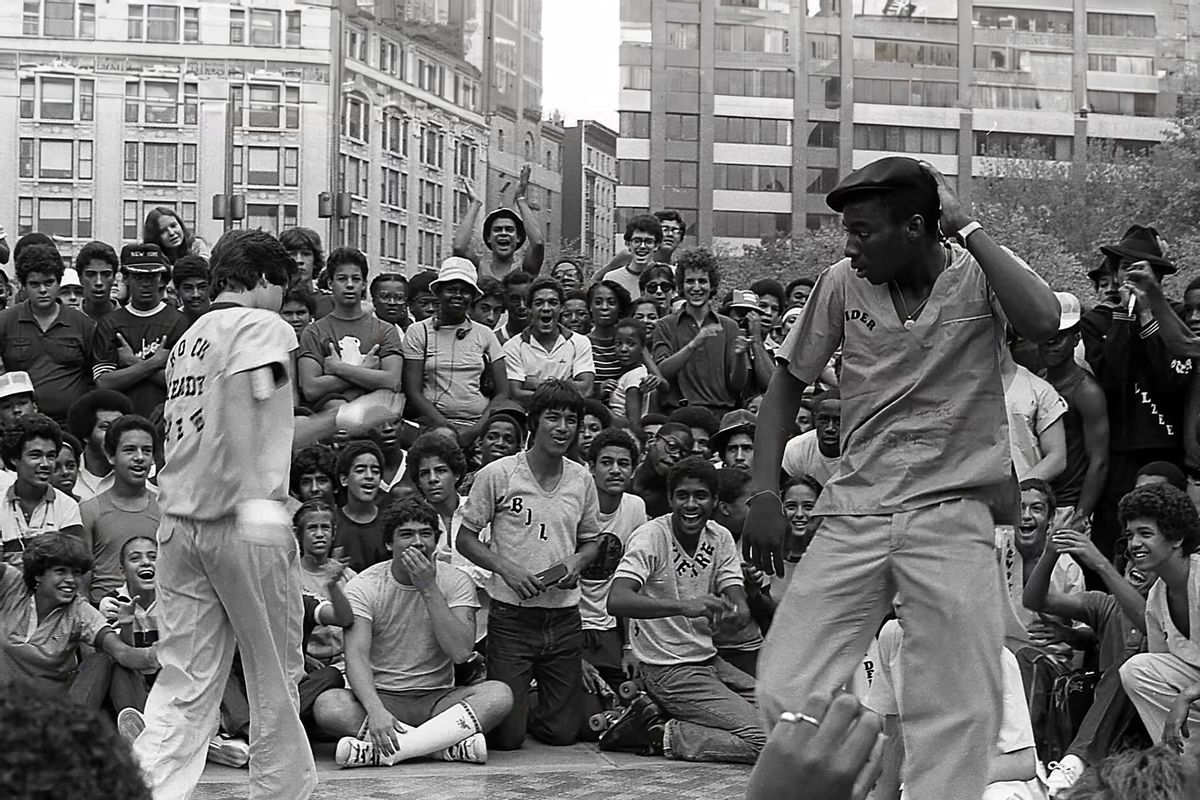

Ask any b-boy or b-girl in the world that name the moment that changed everything, someone says in the Andscape documentary “Breakin’ on the One,” and they’ll cite the battle at Lincoln Center that took place on August 15, 1981.

The face-off between the Rock Steady Crew and the Dynamic Rockers took place in front of an institution considered to be one of America’s greatest bastions of high culture as part of its youth-directed Out-of-Doors Festival. The institution’s administrators included it as a means of appeal to younger kids, but for Rock Steady and Dynamic, the battle became their official introduction to the world – and breakdancing by extension.

Two years later Rock Steady members would appear in the 1983 hit movie “Flashdance,” and “Wild Style,” widely considered to be the first true hip-hop movie, followed by “Beat Street” in 1984.

By then, and for years afterward, it seemed like every kid in the country was throwing down deconstructed cardboard boxes to try to spin, pose and freeze, often poorly. Dancers popped and locked in soft drink commercials, and even Alphonso Ribeiro – yes, Carlton – got in on the action by attaching his name to an instructional manual called “Breakin’ and Poppin.”

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)More than four decades later, as breakdancing is set to make its debut at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, directors Jamaal Parham and Bashan Aquart, who work together as JamsBash, take us back to its Bronx origins.

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)More than four decades later, as breakdancing is set to make its debut at the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, directors Jamaal Parham and Bashan Aquart, who work together as JamsBash, take us back to its Bronx origins.

Clocking in at just shy of 45 minutes “Breakin’ on the One” is mainly through the insights of its originators – who were just middle school kids when they created a dance form that is now a worldwide sport. In our conversation, Parham and Aquart talk about their emphasis on the joy and innovation that is the root of hip-hop, and their desire to give due credit to the OGs of breakdancing and the summertime battle that sent breakdancing global.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

There have been a lot of hip-hop documentaries over the years, although fewer on the art of breakdancing and the history of it. So let’s start with the basic question of, what did you want to bring to the conversation with “Breakin' on the One”?

Jamaal Parham: When ESPN Films and Andscape approached us about this project, and we started digging into the research, for us the thing that was really exciting was I don't think we realized that these were kids. Like actual kids that created a true culture, a moving art form out of nothing, you know what I mean? That was kind of the spark that allowed us to find a way into this world. It's something that you really don't hear about, I think.

"As the genre kind of starts its sort of second, or third or fifth expansion point, it's easy to let the founders – the sort of OGs, for lack of a better term — fall to the background."

To your point about other hip-hop documentaries, last year was the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, and there was all manner of content that was out. But it really never hit home that something this special that was created by the kids that look like us, you know what I mean?

Bashan Aquart: For sure. And I think one of the things we're both keen on is this idea of making sure this moment doesn't get lost. As the genre kind of starts its sort of second, or third or fifth expansion point, it's easy to let the founders – the sort of OGs, for lack of a better term — fall to the background. With every other aspect of entertainment, you can get a sense that you know who the founders were, who the originators were. But not for breakdancing, for the most part. And this became a really great kind of moment to highlight who these guys were, who these kids who are now men were. Then hearing them talk about it is illuminating in the way that when they go back to those moments, they’re still those kids.

I really want to talk a little bit more about the fact that, to your point, these were kids that created a culture. When, I've seen other footage of hip-hop, and this goes back to that whole idea of like the adultification of Black children, that part is almost never mentioned. I mean, I had always assumed I was watching high school kids. But these were middle schoolers!

Parham: Yeah. Yeah. And, it came out of a bonding of community. That's the other thing that's missed is that they were looking for alternatives to the street gangs at the time.

New York was a place that, as you see in the imagery, wasn't a great place to be at the time. The federal government had kind of abandoned the city . . . These kids came together as a means of survival. But I don't know that they knew that it was survival at the time. They were just looking for other kids who had joy like they did. You know what I mean?

To me, that's really special. A lot of the stuff that we do in our art is has this through line of joyfulness and finding the joy in the human experience. And you can just you can see it in the footage. Like, they're coming out of poverty and creating art, but to them it's like, “We're just having fun and dancing. I think Ken Swift [aka Ken James Gabbert of the Rock Steady Crew] says it at the end: It blows his mind that they were just trying to dance and impress a girl, but they ended up creating an art form that's now going to be in the Olympics.

We need your help to stay independent

Aquart: Yeah, it’s almost a matter-of-fact approach in terms of the world that they existed in, which is interesting for us to paint a picture of. But . . . it's so much more about them, going from place to place, picking up different battles in different boroughs and basically attempting to kind of build their own bragging rights. That's what was important to them. And the world around them mattered less because that’s what they came up in. And I think that that's where that kind of sense of joy for everybody else comes in is to say, “Oh, wow, these kids pushed through. And they actually invented something amazing."

Parham: It's almost like an adventure in that way. There's footage in the film of them running out of the subway as they go to Lincoln Center. And it feels like a “Goonies Never Say Die” kind of energy. It's got this just kind of youthful joy behind it that you just don't see anymore. You know what I mean? Everything’s so cynical.

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)I think it was [documentarian] Mike Holman who said there are people who don't realize that this all started in New York. And that surprised me.

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)I think it was [documentarian] Mike Holman who said there are people who don't realize that this all started in New York. And that surprised me.

Parham: I wasn't totally surprised. I mean, I grew up in Los Angeles in the East Coast/West Coast gangsta rap era. So I had an understanding of it. But I can easily see how. There's a sequence in the film where we show when corporate America gets its claws on breakdancing . . . It's this kind of whitewash, like, “We're just taking the part that we like about this, the easy part, the dance part.” But when you remove the culture . . . you don't understand that they come from something, you know what I mean? All these elements are building from a thing.

"To see what breakdancing has done in Asia and in Scandinavia and in Germany, and France, it’s beautiful," said Parham.

There's a portion of an interview that we weren't able to include, but we were talking to, I believe, Ken Swift about why they used the cardboard. There's always cardboard, no matter what the conditions are that they're dancing [in], right? But what he said was, “Nah, we used the cardboard because we were too poor to have a bunch of different outfits. So we only had one dance outfit, but we didn't want to mess it up on the ground." That detail is so culturally specific — like yeah, you're in the summertime dancing on hot asphalt, you don't want to tear your jeans. But I think when it shows up in commercials and movies and TV shows, and that kind of heart is removed from it, that that grit is removed from it, it starts to become separated . . . It's not this urban form of escape, you know?

Aquart: And I think probably the more surprising aspect of this piece was the Lincoln Center of it all, who we've done work with for in the past. When you think of cultural institutions in the city that feature ballet and feature what's considered high art, you don't necessarily connect urban art forms to those institutions. In fact, anytime we talk about the documentary and talk about Lincoln Center, people are like, “So yeah, what’d they have to do with it?” That part of it, I think, is more of a surprise than the kind of elements of hip-hop coming out of coming out of New York.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

The documentary ends by connecting the past to the present of the Olympics. And the debate over, is it dance or is it a sport? Where do you two land on that debate? Can’t it be both?

Parham: We didn't really go in there with an intention. We were more curious about how these guys felt. But I'll say that, I think two things can be true: this can be a dance; you can honor a culture. But you can also still put it on a stage and make it competitive. And maybe that's just me talking, because I'm very competitive in everything. But I think that there is a sense of like, gymnastics has a floor dance component that’s very clearly dance. Figure skating is athletic, but it's clearly based in dance. There’s is a way to make this stuff competitive.

But what I don't want to get lost is that these OGs, the guys who started it, they want to make sure that it's not co-opted and turned into something else, and mutated into a thing that forgets where it came from. You know, Spinner [aka Elio Perez of the Dynamic Rockers] says this in the film: He's like, “Street cred is always going to be more to us than the Olympics will.” And for them, I think that's really true. That's a badge of honor for them, and we need to, as globally as this thing goes, make sure that that doesn't get lost.

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)Aquart: And throughout the piece, there are points where we talk about the economics of breakdancing and how it seems that anytime it's commodified, it had this steep incline and then steep decline. And I think what the doc attempts to do is to be something of a beacon to the people in organizations who are attempting to do that again, to do it correctly to do it with some sense of thoughtfulness and some consideration for the origin story of breakdancing. To not forget where it came from.

Breakin' on the One (Andscape)Aquart: And throughout the piece, there are points where we talk about the economics of breakdancing and how it seems that anytime it's commodified, it had this steep incline and then steep decline. And I think what the doc attempts to do is to be something of a beacon to the people in organizations who are attempting to do that again, to do it correctly to do it with some sense of thoughtfulness and some consideration for the origin story of breakdancing. To not forget where it came from.

And I realize this might be contradicting what you guys just said, but I have to ask: Are you hoping that Team USA takes home the gold in that category?

Parham: Obviously, yeah. I mean, we're always going to root for Team USA. . . . Breakdancing is an American art form. A lot of our work is about telling American stories, and we'd love that. But what we also appreciate is the fact that this is a global thing. And like, USA is not maybe the favorites to win in this competition, and there's something beautiful in that, you know what I mean? To see what breakdancing has done in Asia and in Scandinavia and in Germany, and France, it’s beautiful. It's a true American art form that we've exported around the world. Yeah, yeah.

Aquart: And after getting a sense from the people in the documentary of the general feelings overall, there is definitely a beauty to that. But you can also see why it would be infuriating.

"Breakin' on the One" is now streaming on Hulu.

Shares