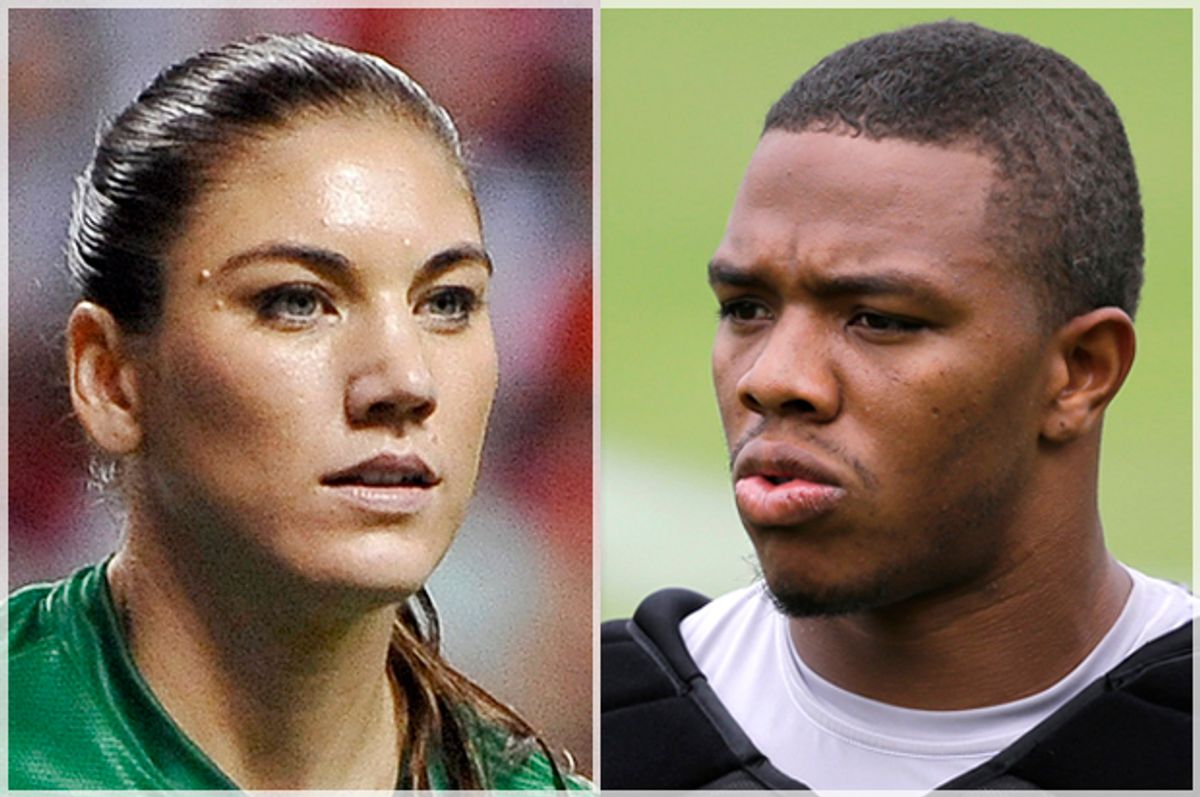

Last week, writers for the New York Times and the Washington Post asked why, as we continue to confront domestic violence and likely coverups within the NFL, "no one" is talking about Hope Solo, a goalkeeper for the women's national soccer team who was this summer was charged with assaulting her sister and teenage nephew. "When Ray Rice, Greg Hardy and Adrian Peterson were arrested, there were loud calls for those players to be suspended," Juliet Macur wrote for the Times. "The response to Solo’s case? The sound of crickets -- except on game days, when it changes to applause. And that’s inexcusable."

A couple things to lay out upfront. First, you shouldn't assault people. Second, it's right to question whether Solo should be on the field while she faces domestic violence charges. (I err on the side of benching players charged with violent offenses while those charges play out, but that's just me.)

That said, while Macur uses the punishments meted out to Rice, Hardy and Peterson to make a point about disparate consequences, I will remind you here that Rice's indefinite suspension was leveled only after video of him coldclocking his partner was released to the public and that Hardy and Peterson were likewise only penalized after the bad press became too much for the NFL to ignore. (Both men remain on paid leave.) And that prior to these high-profile cases, the NFL has systematically ignored the violence of its players in order to keep abusive men playing. And that there are men currently on the field who have domestic violence and sexual assault in their histories. Now having one inept sports league handle domestic violence ineptly does not give other sports leagues permission to do the same, but forgive me here if I'm not persuaded by Macur's use of the NFL as a moral yardstick.

But perhaps the more troubling thing here is the history and context that's been wiped from the slate. Writing for the Washington Post and echoing Macur's essential question, Cindy Boren writes, "Why aren’t more people talking about the fact that domestic violence isn’t simply an issue of men against women?" This is where I throw my hat in with Slate's Amanda Hess and the Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates, who have both skillfully taken on the false equivalences between Solo and Rice, women's soccer and men's football. All of this violence is unacceptable, which is, perhaps, the essential point that Macur and Boren are attempting to argue. But each erases a lot in her vigor to make a one-to-one comparison between these cases, and more broadly, to argue that domestic violence is an issue that impacts men and women in ways that are culturally the same.

Coates lays out the matter of history and power succinctly, so I'll quote him at length here:

In the history of humanity, spouse-beating is a particularly odious tradition—one often employed by men looking to exert power over women. Just as lynching in America is not a phenomenon wholly confined to black people, spouse-beatings are not wholly confined to women. But in our actual history, women have largely been on the receiving end of spouse-beating. We have generally recognized this in our saner moments. There is a reason why we call it the "Violence Against Women Act" and not the "Brawling With Families Act." That is because we recognize that violence against women is an insidious, and sometimes lethal, tradition that deserves a special place in our customs and laws.

This is the tradition with which Ray Rice will be permanently affiliated. Hope Solo is affiliated with a different tradition -- misdemeanor assault.

Men are victims of domestic violence and sexual violence. And I've written before about the unique challenges and stigma men face when coming forward about that violence, and what needs to be done to remove those barriers in order to obtain justice and safety for male victims. But talking seriously about the violence men experience does not require faux outrage over the supposed injustice of the culture finally (albeit imperfectly) talking about the domestic violence that one in four women will face in their lifetimes, or paying attention to how one of the most influential and monied sports franchises in the world has for too long ignored the problem, to borrow the language of NFL commissioner Roger Goodell, in its "own house."

Perhaps we aren't talking about domestic violence in women's soccer to the same extent we are talking about the NFL's violence problem because women's soccer is not a sport with a long history of players being arrested for or accused of domestic violence. Or, perhaps we aren't talking about domestic violence in women's soccer because ... we never talk about women's soccer. Hess makes the point nicely. "But isn’t it more likely that the lack of public pressure in Solo’s case simply represents the relative lack of attention that women’s soccer receives as compared with pro football?," she writes. "A mixed martial arts fighter who goes by the name War Machine is facing 32 felony charges in the brutal beating of his ex-girlfriend Christy Mack. Based on a Nexis search, that vicious assault has been covered in Macur’s New York Times in just one microscopic AP news brief. Might that be because mixed martial artists are less prominent cultural figures than NFL stars?"

So this is the trouble, in general, with false equivalences. They do a great disservice to both of the issues drawn in through the comparison. Hess calls the conversation demanded by the Times piece myopic, and I'd agree. A conversation about whether or not Solo should be on the field right now does not require smug finger wagging about inconsistently applied standards of outrage, it requires a grappling with how sports leagues handle violent offenses. (That's a far more complicated conversation to have than many of us are willing to concede.) Condemning what Solo is alleged to have done does not require erasing a history in which men have systematically used manipulation and physical violence to dominate, humiliate and kill women. And scrutinizing the top brass within women's national soccer for their calculus around Solo does not require us to insincerely argue that women's soccer and men's football are sports that receive equal attention in the media -- that somehow it's just this one time that the public has fallen silent in an otherwise robust conversation about the women's national soccer team.

We are often asked to divert our attention from the systemic violence that women face with cries of "women do it, too" or "sometimes women lie about abuse." When this happens, we are asked to take these claims -- statistically and historically different -- as the same. These are derailing tactics, more often than not. When we read about sexual assault, we are asked again and again to consider the incidence of false allegations. When we learned each new detail of Ray Rice's brutal assault, we were asked to remember that Janay Rice hit him too. And now that we are using the NFL as the lens through which we can view our culture's deadly domestic violence problem, we are being accused of unjustly focusing our anger. It seems that the only time people want to talk about the violence that women commit is when we seem to, for once, be talking about the violence that women experience.

Macur and Boren seem interested in "equality." That the public have the same outrage over Solo's alleged violence as we do over Rice's brutality. I'm a fan of equality. But the conversation unfolding right now around the NFL and domestic violence is a conversation that, to me, centers on justice. (I was reminded of this crucial distinction again this morning by Brittney Cooper's excellent analysis of the "future of feminism.") It's bigger than a handful of incidents, it's bigger than the Ravens or the Panthers. It's about the NFL, and it's about the rest of us. Grapping with that requires an examination of context, history and power, precisely the elements that are lacking from the "where's the outrage" critique Macur and Boren pushed.

Women's soccer is not a symbol for our culture's ignorance and indifference to domestic violence. Neither is Hope Solo. She's a woman who has been charged with assaulting members of her family -- charged with domestic violence -- and if that's the crime she committed, she will no doubt face consequences. But she isn't the face of domestic violence in a country where one in four women will experience such abuse in her lifetime, or where women account for two out of three murder victims killed by an intimate partner. So asking, "where's the outrage" might make for a strong headline, but it entirely misses the point of the current cultural reckoning around the NFL and domestic violence. Treating these cases as the same thing might be "equal," but it's certainly not justice.

Shares