I didn't set out to marry a doctor. If you'd asked during my Match.com days, I would have told you I didn't even like doctors. They're bossy, skeptical, self-important and weirdly nervous about feelings. They're always sure they know more about your body than you do -- and they're only sometimes right. Also, they have bad taste in shoes.

When I moved to Seattle in my late 20s, I told myself I was ready to look for a mate, a viable life partner. I then proceeded to fall for an illegal Canadian alien, a 22-year-old, a married man, a more-or-less married man, and a guy who lived in Kansas. A woman I'd met at a neighborhood cafe hypothesized over coffee that doctors make "the best mates," but I had my doubts.

The only physicians in my life were the one at the women's clinic and the ones on "Grey's Anatomy," which I'd taken to watching on DVD in obsessive late-night marathons around the time I turned 30. Like any other writer (and, at the time, filmmaker) I was intrigued by the interpersonal dynamics and the minutiae -- why did surgeons look down on everyone else? Why were doctors so lackadaisical about condom use? Why didn't they ever lock the supply closet when they went there to have sex? Taking my cue from the surgical residents themselves, I'd stay up into the wee hours. But instead of trying to chase down the best surgeries, I was trying to chase away my loneliness, my heartache, my worry that I'd never get married and have a baby.

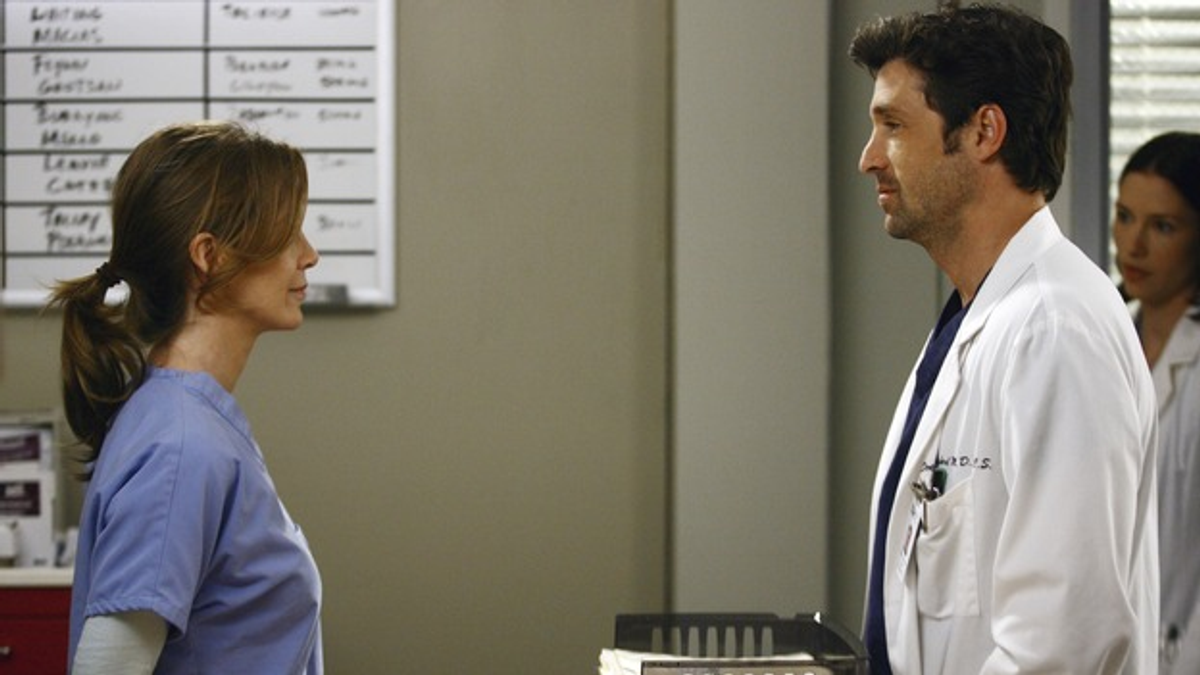

Wary as I was of actual doctors, I lusted after the fictional physicians of Seattle Grace Hospital the way a barista lusts after the perfect espresso pull or a Pacific Northwest cat lusts after just-caught salmon. I loved perfect-haired Dr. McDreamy as much as the next person, but honestly -- male, female, resident, attending -- it didn't matter. If they could stay up all night having crazy sex and then perform successful heart or brain surgery on a toddler the next morning, I wanted them. Sure, they were bossy -- but to each other, not to me -- and they talked about their feelings quite a bit. Even when they announced they didn't want to talk about their feelings, they sat together silently, clearly processing their feelings, which was almost as good. They were smart, sexy, a little wild and a lot sassy -- who cared what their shoes looked like?

That said, they didn't strike me as "the best mates." They were always at work, always thinking about work, and always wanting to work. Plus, they didn't have the best track record, fidelity-wise.

The show's debut coincided with my move into one of Seattle's federally subsidized low-income artist-housing units. Most of the men I met in my job as a part-time filmmaking instructor and at social functions in our building wore Utilikilts or had Asperger's syndrome or claimed to be "born polyamorous" -- or often all three. I wanted to branch out but didn't want to necessarily have to go out. God bless the Internet. I could spend my evenings at home in my favorite leggings with my "Grey's Anatomy" "friends" while my online profile did all the loathsome small talk and weeded out the least suitable suitors.

Given my paltry income, lack of health insurance, tendency to need therapy, and love of all things Anthropologie, I probably should have been dreaming about marrying a real-life McDreamy, but it didn't occur to me -- certainly not consciously. Trader Joe's Three Buck Chuck wine suited me fine, and I enjoyed making art from junk I found on the street or purchased for 69 cents at Goodwill. Being "Mrs. Dr. Somebody" was not on my radar.

When I met the man who would become my husband, I didn't know he was a doctor. His profile was brief and vague and revealed only that he had an advanced degree and had attended a Montessori preschool. From one of his pictures in hiking boots and cargo shorts on some sort of large hill, I guessed he might be a high school science teacher -- the kind with a fondness for slightly-too-long nature walks and an endearing overappreciation of the life cycle of the fruit fly.

Had I known he was a doctor, there's a chance I wouldn't have ever agreed to go out with him. I'd met up for drinks and snacks with a doctor once, only to discover that I would be drinking and snacking solo because the doctor ate (and drank) on an every-other-day schedule ever since he'd read a study in which rats who were fed this way lived longer.

The Montessori guy took me out for a picnic dinner -- of which we both partook -- and at some point between the BLTs and homemade lavender shortbread I coaxed out of him the fact that he was an academic emergency medicine doctor. "Like in 'Grey's Anatomy'!" I chirped, displaying my vast knowledge of the American medical establishment. He was quick to inform me it's "not like that at all."

Of course not! A real neurosurgeon would need a nap between the crazy sex and the brain surgery.

Then it dawned on me that this guy might be my own personal Dr. McDreamy. It didn't matter what a teaching hospital is like on television -- this guy could be my own personal portal. The longer we dated, the more I would learn about the interpersonal dynamics and the minutiae.

I'd always thought my feelings of distaste for doctors was mutual. They always seem stubbornly wary of my stubborn wariness -- as if by declining their samples of Prozac and asking for a recommendation for an acupuncturist, I'm calling into question the foundation of their livelihood. Which I only sort of am. But this doctor wanted to keep seeing me -- over and over.

Even though he's bossy and weirdly nervous about feelings and argues with me when I claim to have a symptom of something (You don't have a migraine, just a tension headache... You're not getting a cold -- you're probably just tired... You're not PMSing -- you're just insane), I fell in love. Three years (and one baby) later, I still know almost nothing about what it's like to be a doctor. It turns out that working in the E.R. all day is as exhausting as it looks on TV, and the last thing you want to do when you come home is to talk about it -- especially about how you feel about it. Is it really that hard to tell someone they have cancer? Is it really that gross to disimpact someone's bowel? These questions do not need to be asked. But there is a distance between my doctor husband and me -- a distance created by the psychological difficulty of telling someone they're rapidly dying, the terror of pulling a knife out of someone's skull, the profound sadness of the heroin addicts, the entrenched alcoholics, the inexorable march of time. I want to know about these things, what it feels like to be immersed in them every day, but I've learned to hold my tongue -- not because it's the "right" thing to do but because peppering my husband with questions gets me nowhere good. When he comes home from what's obviously been a hard day, I now offer him a drink and suggest -- not unkindly -- he go to bed early. I then don my favorite leggings and curl up on the couch to watch some other Seattle doctors provide a portal into my husband's life. And sometimes the next morning over a cup of strong coffee he tells me what's on his mind -- unasked. The best kind of mate.

Shares