The list of rock and roll’s canonical live albums has a stubborn insistence, it seems, on concerning itself with works from the 1960s and 1970s. We all know some version of the list: James Brown’s "Live at the Apollo," the Who’s "Live at Leeds," the Stones’ "Get Your Ya-Ya’s Out," Jerry Lee Lewis doing his thing at the Star Club. It always struck me as odd that there was basically nothing from the 1980s. This wasn’t helped out by the fact that a band like the Stone Roses never released a concert recording, but surely someone could have stepped to the fore and said, “hey, let’s drop this on you, we belong up there.”

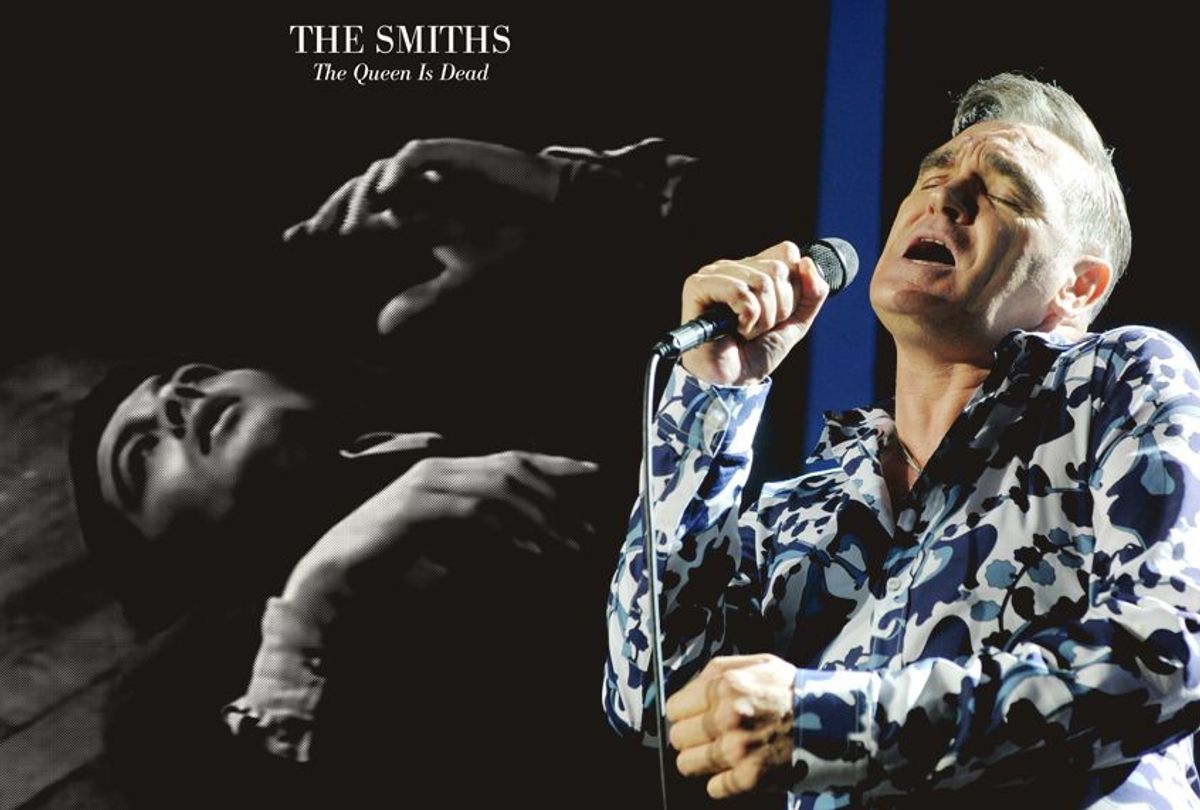

It wasn’t New Order, it wasn’t the Happy Mondays, it wasn’t the Replacements, and until now, it wasn’t the Smiths. But we have a game-changer, folks, thanks to a live set tucked away on Warner’s reissue of the Smiths’ 1986 album, "The Queen Is Dead."

Speaking for the studio release: you probably know it as the Smiths’ best studio creation, a core disc not just of any indie collection, but any popular music collection period, the kind of record that were it a building would have a plaque out front detailing its historical significance. It’s held up as an emo touchstone, but I always thought that was so far from the point as to have nothing to do with a point, right from the way the album starts, with the title track, whose guitar riff is so cleaver-sharp that it sounds like it could part all of your limbs from your body — in a good way, one that would help them to participate in a dance more freely.

But what you’re going to want to do if you pick up this reissue is to get the Super Deluxe Edition, because it is there that you will find a concert dubbed "Live in Boston" on disc three, which dates to the Smiths’ U.S. tour during the summer of 1986 — August 5, to be exact.

The Boston thing is pretty misleading. I was 10 at the time, starting to fancy myself someone who knew something about music — I did not — because I had ditched the Air Supply of a few years before (I am still open for ribbing on that one) and would listen to the Beach Boys, Def Leppard, Culture Club. Regarding those latter two bands, I even had little buttons, because if you liked cool bands back then and you were a prepubescent know-nothing, you got buttons.

We lived in a place called Mansfield, which people don’t know, so you have to say it’s next to Foxborough, which people only know because that’s where the Patriots play. My backyard was nothing but forest. You could walk through the woods for miles. This forest was called, somewhat mysteriously, like the brothers Grimm had provided a titular loaner, Great Woods. And so it came to pass that a concert venue of the same name was built in this forest, though going to concerts was beyond my ken as a button-collecting, “Karma Chameleon”-lyric-citing 10-year-old.

On the night of August 5, 1986, I was sitting out on the porch at night, probably having just watched the Red Sox, busy planning the Huffy-based shenanigans I’d get up to the next day, when I heard a ghostly voice — I remember thinking how disembodied it was — wafting through the trees. For, you see, those woods weren’t so big that we couldn’t hear the strains of whatever concert was going on -- but this was louder, like this came from an act that trafficked in volume. The song had to do with a youth and something stuck in his hip or something; I didn’t know just then that it was “The Boy with the Thorn in his Side,” but I knew, on that summer night, that these guys were hardcore rockers. The next day, I learned they were the Smiths. And that was the first time I heard them.

Later in life, I tracked down a bootleg of that “Boston” show, with its fuzzy sound, a nice replication of my through-the-forest first taste, but you need to hear this pristine soundboard recording. Too often the Smiths are co-opted to be a band that is all about, to use a modern term, your “feelz,” but in my thinking, their bond with emotions — and your own specific set of emotions — only comes into focus when you fully hear their no-quarter approach to instrumentality.

Johnny Marr, for example, was the indie version of Hendrix, but with more nuance. The opening “How Soon Is Now?” on "Live in Boston" contains a guitar intro that one person should not be able to play on his or her lonesome. It’s downright Wagnerian by way of Phil Spector, far more sophisticated than anything that Jimmy Page achieved with a world of guitar overdubs at his back.

By the time Morrissey enters with his vocal, a kind of battle has already been won; that strange, haunting, eldritch-but-enveloping voice then becomes a sort of auditory fist punch, the sound of one’s very self, pressed into service by this Mancunian band, asserting itself. You practically feel like you’re making the music, simply because you feel like it belongs that much to you. They pull you in that deeply.

The band itself was amazingly symbiotic. They have real jazz pop at times, like an Horace Silver-led group, thanks to Andy Rourke on bass and Mike Joyce on drums, who jointly enliven “I Want the One I Can’t Have” and “Is It Really So Strange?” on this particular tape to the point that you get a sense of that same rhythmic core that we find as the basis for a lot of the best Stax tracks.

And then there is Morrissey, always in his element in live performance, thanks partially to just how flat-out well the guy could sing. Certain rock singers are just technically great singers regardless of genre. Elvis, Paul McCartney. Moz is is in with that crew, and even this former 10-year-old, listening through the trees, knew that something was up, something life-changing, when Morrissey began to intone “I Know It’s Over.”

Even from that vantage point, there was a theatricality to it that didn’t feel theatrical — as in, not something that trod the boards. It felt theatrical like life does when you imagine someone watching you live your own, forming their own thoughts and conclusions about what you’re doing. I didn’t know there could be a song version of this.

In the interest of full disclosure, it’s worth noting that this new set is not the full set, if you know what I mean. The bootleg, made by an audience member, contains the whole concert, but that’s some real Snap, Crackle, and Pop fidelity. "Live in Mansfield" is more like an album that just happened to be made from a gig, like those woods were the recording studio, those in attendance the engineers, and a boy on a porch left to play producer as he fiddled around with how to best proceed with the waves of new emotions that had just come in like so many canisters of session tapes.

Shares