Anyone expecting the memoir by Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr to sound as rough and macho as Keith Richards’ “Life,” or as verbally fancy as the one by his old bandmate Morrissey will be startled by “Set the Boy Free.” The “autobiography,” as it’s called, describes a sensitive but reasonably well-adjusted boy growing up in Manchester, England, and fascinated by guitars before he had really heard them. The book moves through his years with the tumultuous and era-defining Smiths and into his working with artists like The The, Bryan Ferry and Modest Mouse. It also tracks his building a family and moving back to Manchester after a stint in Portland, Oregon.

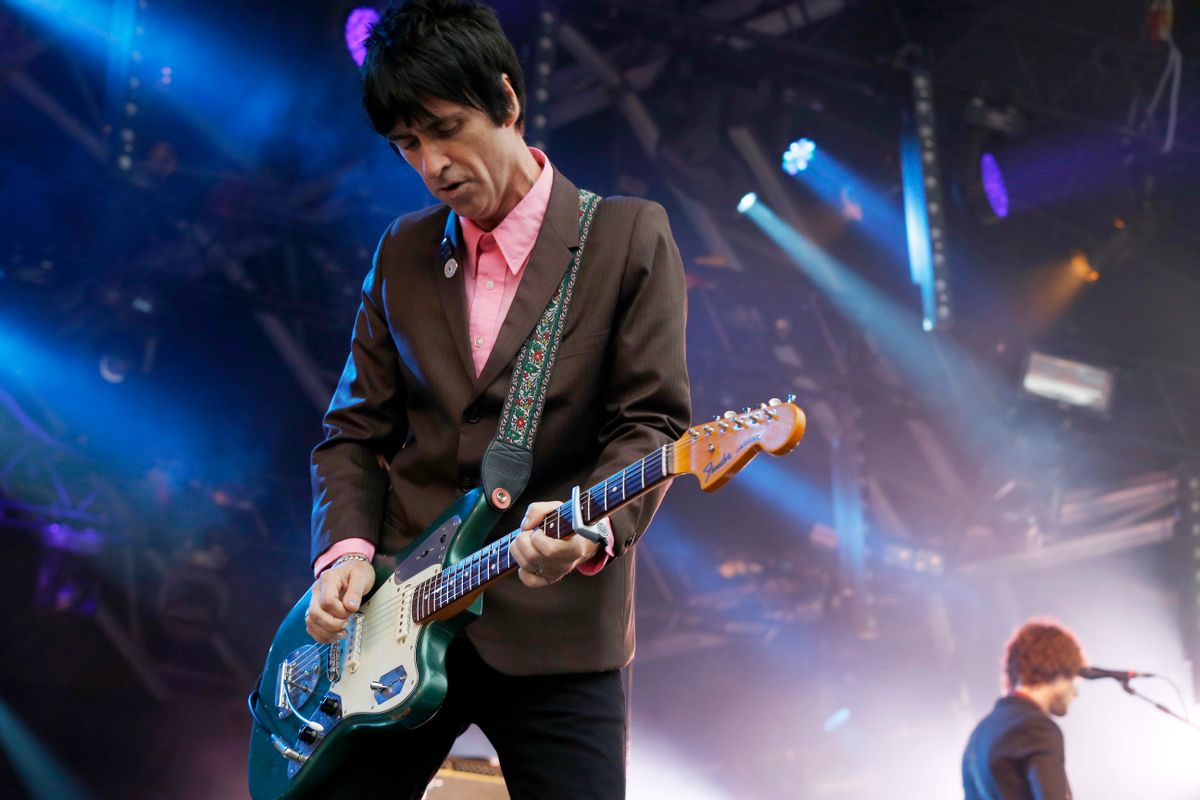

Marr spoke to Salon from Los Angeles, the morning after he appeared to a sold-out audience at an old Los Feliz cinema with his Fender Jaguar and the deejay Jason Bentley as interlocutor. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

It’s striking to read how Irish-Catholic your upbringing was. And your most famous band is stocked with people named Marr, Morrissey, Rourke and Joyce. No way around it: This is a bunch of Irish boys.

And the band I had before that was Marr, Kennedy, Rourke and Durkin. That was even more Irish.

Yeah you’re not really leaving a lot to the imagination with that one. We read about your childhood, your family, your trips to Ireland. Another great English band — I forget what they were called — was led by a couple of guys named Lennon and McCartney. So there is a lot of Celt in “English” rock ’n’ roll. And one one of the great, innovative bands of the late ’80s and early ’90s was My Bloody Valentine, also a bunch of Irish kids.

What makes the Irish so brilliant with music? Did those origins shape your decision to become a musician, or your taste?

Well, those musicians you mentioned, they’re not too far form first or second-generation folk people, or country people. My people, my parents, my aunties and uncles — I was first-generation British…. All my folks and family came over as really young kids. When I was growing up, I saw them as music fans, and they still bought a lot of records. It wasn’t all trad stuff, either — they bought a lot of pop stuff.

I watched people be fans first and foremost, as they grouped around all these instruments, and this culture of singing and playing when you had a few drinks going on. Which was often. Which was probably the same for Kevin Shields (of My Bloody Valentine) and Mani from the [Stone] Roses and Kevin Rowland from Dexys Midnight Runners. And the Gallagher brothers [Oasis].

There’s a real culture in the UK for kids who grew up with immigrant parents. We all grew up with parents and grandparents who, much like in any folk tradition, played music at home for entertainment, mostly because they were broke. They weren’t people who were gonna go to cabaret clubs or to see artists or to supper clubs. They were people who literally worked in the fields… It’s the same in parts of the Ukraine and Eastern Europe. The music has a similar sound to the Eastern European sort of music.

In an early part in the book you talk about falling in love with music as a kid. Unlike other people, who hear the voice or the words or something else, you hear the guitars. You connect with music in a very direct way; yours is some of the best writing I’ve ever seen about how deeply music can get into you.

You use the phrase “beautifully melancholy” for the sound you went looking for in music. You don't seem like a particularly sad guy. Some of your bandmates maybe do, but you seem like a pretty well-adjusted bloke. What is it about melancholy that draws you, and is it still the way you hear and favor music?

Yeah. It spoke to me about the other side of life — which is a certain kind of striving and discomfort and dissatisfaction. Which, I guess, now that I’m older, I’d define as what’s called ‘the human condition.’"

Ha — yeah, a fairly major part of our lives, isn’t it?

Yeah! And as a little boy I had a lot of that going on, even though I am a seemingly balanced person — and, I guess, quite contented. But if I hadn’t found a way of expressing that beautiful melancholy, I might not actually be so okay with those things. So, really, about 50 years of being able to express that and explore it in music -- I guess it’s in me, or I wouldn’t make that kind of music, certainly not with the Smiths anyway.

I was very, very sensitive as a little boy — it was only when I moved out to the suburbs, out to the projects, that I got a chance to reinvent myself. That came through music and culture. I was just reflecting what people were throwing at me, really. I arrived as a little boy who played the guitar, and I saw that as my chance to get tough, you know?

There’s a song by the Beatles called “There’s a Place,” and another by the Jam called “The Place I Love.” I’m not sure what they’re about but to me they've always seemed to speak to the idea of disappearing into music. It’s the same way I think of a lot of the Smiths’ music. Where you could get lost in it.

Yeah — that’s a nice thing, you know. We did that on tunes like “That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore,” and particularly on a song on our last album called “Last Night I Dreamt Somebody Loved Me.” Which is obviously very dramatic.

I suppose I just tapped into the beauty of that personal expression, that personal emotion. I never really saw it as sadness. I just saw it as a proper human feeling. And if you’re able to set that to a melody, and an atmosphere, it’s a really incredible thing. And an example of music being able to say things better than words.

Shares