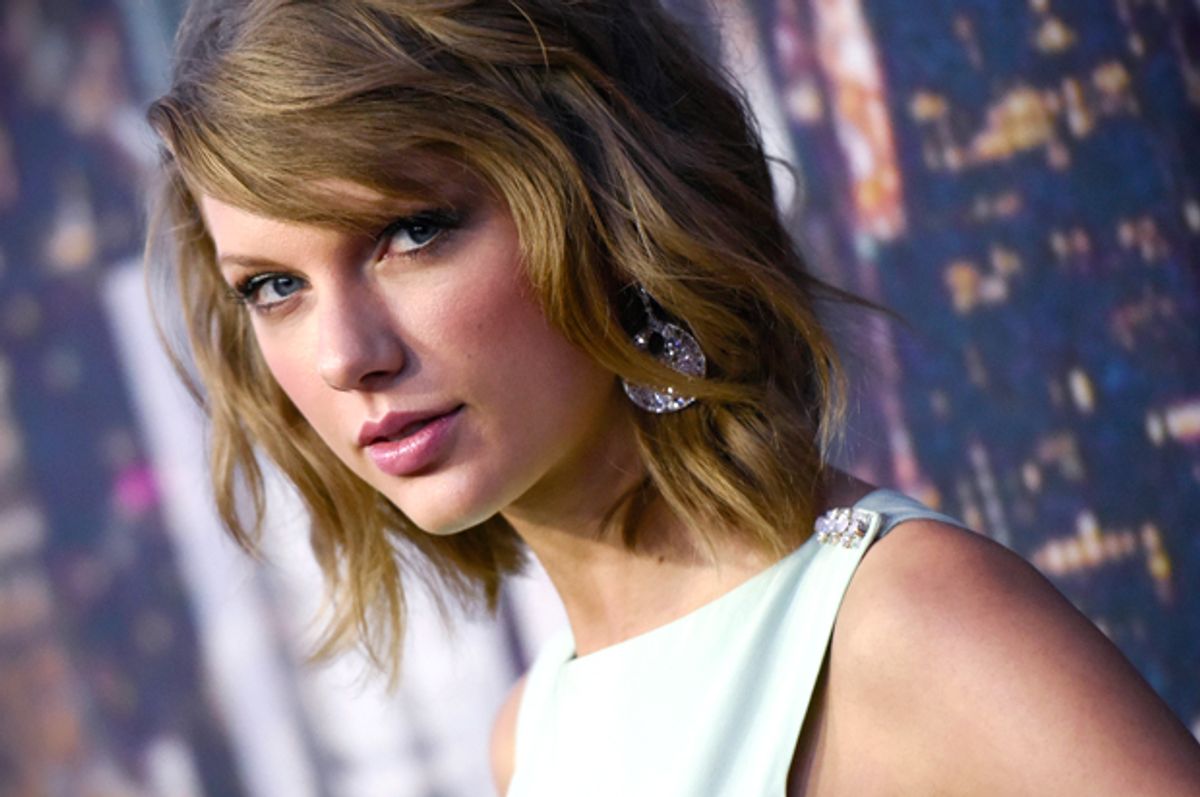

Over the last few years, Taylor Swift has become one of the two or three biggest pop stars in the world. She has accumulated no fewer than four homes (including a $3.5 million place in Beverly Hills and a $20 million Tribeca penthouse) and drawn enormous press and media attention. She’s still on the cover of lots of magazines and we’ll probably see her there far into the future.

On its release last year, her “1989” record became the biggest selling album in more than a decade, at a time in which record sales have been way down. She became, according to Business Insider, “the first woman to have three albums sell more than 1 million copies in a single week.” The album has now sold more than 4 million – the kind of number we thought, in the age of file-sharing, we’d never hear again.

Swift’s current tour will take her to stadiums all over the world, including Metlife Stadium in New Jersey, capacity 82,600. Her net worth is roughly $200 million – that’s about 3,550 times the median net worth of an American household. By every available measure, she seems to be doing pretty well, and at 25, she’s probably just getting started with her world domination.

But to the New York Times, she is, apparently, an “underdog.” The paper of record used the term twice in its review of her show in a relatively intimate 13,000-seat arena in Louisiana and pulled it out for the headline as well: “On Taylor Swift’s ‘1989’ Tour, the Underdog Emerges as Cool Kid.”

Well, Taylor Swift may be a lot of things, but we’re not really sure “underdog” is one of them. Let’s back up a little bit.

Like a lot of country singers – that’s how she first broke in – Taylor Swift grew up on a farm. It wasn’t a subsistence farm in the rough part of Kentucky but a Christmas-tree farm in Pennsylvania. “Her mother worked in finance,” a New Yorker story says, “and her father, a descendant of three generations of bank presidents, is a stockbroker for Merrill Lynch. (He bought the tree farm from a client.)” In Swift’s hometown, she told the magazine’s Lizzie Widdicombe, “it mattered what kind of designer handbag you brought to school.”

So let’s acknowledge that she began life with a slight leg up on the privilege escalator. But the playing field is about a get a lot less level: “When she was ten, her mother began driving her around on weekends to sing at karaoke competitions,” the New Yorker tells us. “Then she persuaded her mother to take her to Nashville during spring break to drop off her karaoke demo tapes around Music Row, in search of a record deal; they didn’t succeed, but the experience convinced Swift that she needed a way to stand out.”

When Swift was 14, her father relocated to Merrill Lynch’s Nashville office as a way to help dear Taylor break into country music. As a sophomore in high school, she got a convertible Lexus. Around the same time, her dad bought a piece of Big Machine, the label to which Swift signed.

This is hardly the first case of stage parents or a rich kid breaking into the music world. And along the way, Swift has worked hard, behaved reasonably nicely, and so on. But why are we describing her as someone who’s triumphed over adversity?

Part of this is because of a critical/journalist school that worships money, popularity and fame: Unlike previous generations of critics, or the traditional journalistic mission to “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” Poptimists like the New York Times' Jon Caramanica don’t buy the old small-is-beautiful premise. And what better way to reconcile the contradiction – to inject a bit of rebel cool into the story – than to make a millionaire daughter of the plutocracy into an underdog?

Specifically, the review refers to a much-quoted song, “We are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” which is about her relationship with one or another celebrity actor or singer or Jonas Brother. Here's Caramanica:

In the song, she’s lashing out at a dunderheaded ex: “You would hide away and find your peace of mind/ With some indie record that’s much cooler than mine.”

Indie rock – and punk and alt-country, and left-of-the-dial R&B and related genres that are uncomfortable with corporations or consumerism – is exactly the kind of thing an offspring of Wall Street like Taylor Swift is not going to respond to. So does her dissing a celebrity ex make her into an underdog? To a poptimist, maybe.

But this kind of thing is especially offensive since there have actually been plenty of musicians who really were underdogs.

Johnny Cash was raised by poor cotton farmers during the Great Depression. John Lennon’s mother and father abandoned him. Jimi Hendrix’s early life was a nightmare that involved shoplifting food so he could eat. For decades, the average blues and country musician came from poverty or close to it. Billie Holiday was jailed, as a teenager, for prostitution. And so on.

And even for the musicians raised middle-class – many were – a life in music has involved real risk and suffering. The punk band the Mekons has bounced up and down, from label to label, for decades. Jason Molina, who made transcendent records on tiny labels with Magnolia Electric Company until alcoholism took him down two years ago, never found a substantial audience. Chan Marshall of Cat Power recently filed for bankruptcy. In a post-label world where piracy has shredded artist’s earnings, just about everyone trying to play music professionally below the superstar label could be considered an underdog.

Somebody should tell the New York Times: Just because the Jack Black character in “High Fidelity” doesn’t think you’re cool doesn’t mean you’re an underdog. He doesn’t call the shots anymore, and really, he never did.

Shares