We flew from New York City to New Orleans on November 28, 2016, my father, my mother, my husband, my two little girls and I. Our rental car followed the path of the Mississippi northward, snaking past suburbs and swamps, tin-roofed shacks and dirt roads until we reached the Gillis W. Long Hansen's Disease Center, formerly known as the Louisiana Leper Home, in Carville where my dad had once been a patient.

In 1954, at the age of 16, my dad was living with my grandfather in the Bronx when he was diagnosed with Hansen's Disease, the preferred designation for leprosy. He was sent to Carville where he stayed under federal quarantine for nine years, until he was cured and discharged in 1963. Fifty-three years later, he was going back for the first time.

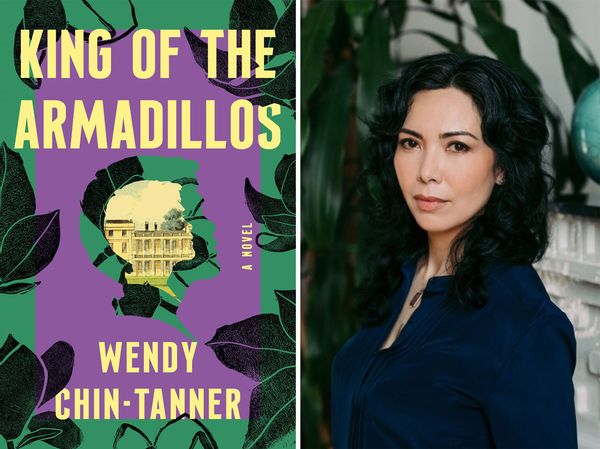

For my dad, our journey to Carville was a bittersweet homecoming. For me, it was both research trip and pilgrimage. I'd recently started writing my novel, "King of the Armadillos," inspired by his experience, and he was helping me access material from the archives of the National Hansen's Disease Museum. Located on the grounds of the former institution, which is now partially occupied by the National Guard, the museum invited my dad to record his oral history, so we decided to go.

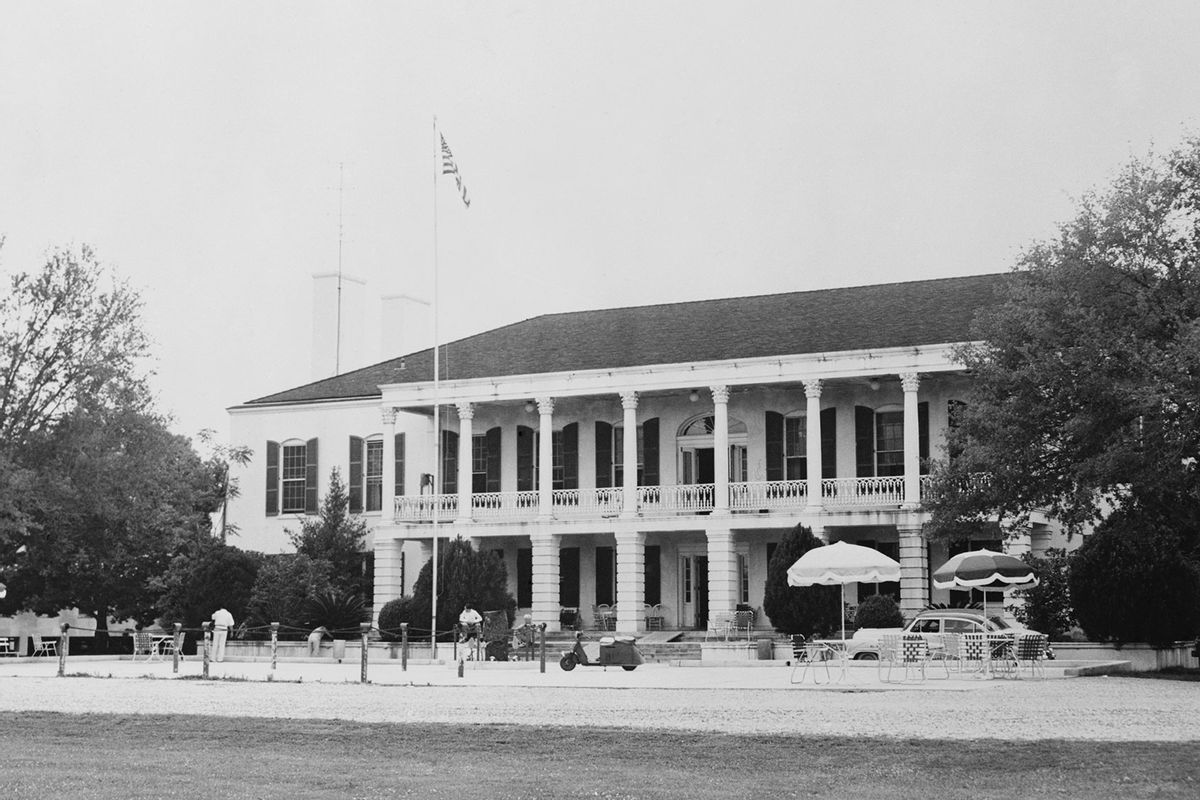

My husband stopped the car in front of a set of high, iron gates. A guard in military uniform directed us past a white plantation house with sweeping balconies and Corinthian columns, through an avenue of live oaks, old and gnarled, and draped with Spanish moss, to the infirmary. It had been converted into military conference accommodation where we were staying.

Founded in 1894 on the grounds of an abandoned sugar plantation, the 330 acres of the institution were well-manicured with neatly mown lawns, flowering bushes, ornate gardens, a lake, a golf course, and sprawling fields amid the Victorian-style dorms, covered walkways, and numerous amenities that made Carville look more like a prep school than a leprosarium. But just as it had been when my dad was there, all that beauty was surrounded by a barbed wire fence.

As we approached the broad face of the 1930s federal building that had served as Carville's hospital, I tried to catch my father's eye, but I couldn't read his face. He was looking down at my two-year-old daughter, guiding her up the concrete steps.

"Is it the same?" I asked him, opening the door. "It smells different."

I thought he might have been talking about the pollution, the emissions from the nearby chemical plants that gave the air an unnerving metallic tang.

"No," said my dad. "I mean it doesn't smell like a hospital anymore."

When he arrived at Carville on November 12, 1954, my dad had gone straight to the infirmary, too. After a two-day train ride from Grand Central Terminal to Union Station, he was as exhausted and terrified as "a poorly nourished, chronically ill looking Chinese boy" could be. Sister Victoria, one of the Daughters of Charity who did the majority of the nursing at the hospital, made that observation during my dad's intake interview, which he was obliged to give before submitting to a battery of tests—X-rays, labs, a physical, and biopsies of his lesions.

In the interview, my dad told her that "his father served in the US Army. His grandfather who lived in New York returned to China and was killed by the Communists. This occurred because this man was known as a Chinese who had been in the United States for a long time, and therefore was likely to be a sympathizer with American political principles."

You value personal and political stories

Everything he said was true, but I imagine he must have emphasized those details to make our family sound more patriotic.

"What name will you be taking?" Sister Victoria asked.

My dad was confused, and she explained that most new patients chose Carville names to spare their families from the stigma of their diagnosis. He chose to keep his own.

So many of my dad's stories about his youth were set at Carville that I'd been imagining it for my entire life, but he never said much about his time in the infirmary. Once, when I was little, I asked point blank about the twin scars running up the insides of his arms like tire tracks on a sandy beach. As I traced one of them with my finger, he answered simply that he'd had an operation on his nerves. I let my hand fall to my lap. His words were matter-of-fact, but his tone made me feel like I shouldn't have mentioned it.

In his admission work-up, Dr. Riordan wrote that my dad had "loss of sensation on the ulnar aspect of both hands… and he has had recurrent bouts of neuritis. I think he will benefit by having an ulnar nerve transposition."

He must have been in excruciating pain, but he's nothing if not stubborn.

"Dr. Riordan recommended surgery," Sister Leonara wrote in an Interval Report, "but patient refused."

Throughout his medical records, I can see glimpses of who my dad is, who he's always been—a complex soul who can be both affable and combative, cooperative and recalcitrant, depending on his mood. Over the next few years, his nursing notes were peppered with remarks like:

"Called but did not come in for examination as requested." "Remained in bed entire day. Still refuses to talk to anyone."

"Does not try to answer questions even when normal and comfortable. Whether this is part of an anxiety syndrome associated with his illness or due to some outside social problem which he has not felt free to relate to myself or the staff, I can't say at present."

Three-and-a-half years after his initial examination, Dr. Riordan wrote on April 30, 1958, that "this patient still shows the involvement that he showed before… If he has changed his mind and wants to have the ulnar nerve transposition, I would suggest that it be done as soon as possible."

My dad held out for almost another month, but on May 21, 1958, the operation was finally done.

Throughout his medical records, I can see glimpses of who my dad is, who he's always been—a complex soul who can be both affable and combative, cooperative and recalcitrant, depending on his mood.

When he arrived as a minor, my dad had even fewer rights than the adult patients since my grandfather had signed release forms agreeing to whatever medical treatment the doctors deemed necessary. It strikes me as somewhat remarkable that my dad was able to delay his surgery by sheer force of will. Though he lacked agency, his intransigence proved to be an effective tool of resistance.

At the same time, the administration's apparent tolerance for patient self-determination was a hard-won result of the patient campaign to change Carville's institutional culture from that of a hospital to a community. The de facto leader of the movement was Stanley Stein, a former pharmacist from Texas, who founded The STAR, Carville's patient-run magazine, shortly after his arrival in 1931. The magazine's mission was to shine a light on the disease to humanize and restore dignity to its sufferers.

Though blind, claw-handed, and unable to walk without a cane, Stanley was an uncommonly charming man with a knack for befriending famous figures like Hollywood star Tallulah Bankhead, who became The STAR's most zealous patron, badgering her industry friends to subscribe. The magazine grew from a two-page mimeographed hospital newsletter to a well-respected Hansen's disease news venue read by people in over 130 countries around the world.

My dad met Stanley during his first stint at the infirmary.

"We shared a room," he told me recently. "We talked about politics and history, like the fall of the Roman Empire. And musicals. He loved Broadway."

When he was "discharged to the colony," my dad joined Stanley's roster of volunteers who read everything out loud to him from correspondence to proofs of articles. Soon, he started volunteering at The STAR office, too, where he learned to set linotype and work the printing press, churning out up to 92,000 copies.

Getting the issues out to subscribers was a laborious process, made even more so by the risk that they might be destroyed with the outgoing mail, which had to be "disinfected" in a lab with dry heat before leaving the institution. Occasionally, a technician would forget to turn off the machine and the bags of mail inside would be burnt to a crisp.

Once, in the mid-1950s, after multiple complaints, Stanley sent my dad to the lab to check on the outgoing issue. The stench of scorched paper, the good smell of the ink gone acrid, hit him before he saw the blackened remains of the magazine. He took one out of the bag, and it crumbled to ash in his hands.

There was no scientific reason for sterilizing the mail just as there was none for quarantining patients. More than 95 percent of all people have natural immunity to Hansen's, which is only mildly communicable even to those with susceptibility, and since 1941, it has been entirely curable. The only possible reason was to assuage public fear, which further perpetuated misinformation and stigma around the disease. Nevertheless, the policy wasn't abolished until the late 1960s.

At my dad's exit interview, his counselor advised him to keep Carville a secret so he could avoid the stigma it carried and focus on his life ahead. And he did.

When we weren't busy in the archives, my dad and I walked the grounds. At the dorms, he pointed out the window of his room in House 29, averting his eyes from the old cemetery at the center of the quadrangle. Its weather-worn headstones were a reminder of how, in the not-too-distant past, Hansen's disease was a death sentence. I couldn't look away.

When it began to rain, we ducked into the recreation center. Upstairs, he showed me the ballroom where they'd held all their dances.

"We had a lot of balls," he said, "but the biggest one was on Mardi Gras."

Along with all the other patients, my dad enthusiastically participated in the Mardi Gras celebrations, constructing floats for the parade, making masks, decorating the ballroom, and performing special numbers with his barbershop quartet.

One year, he was a duke of the royal court while his crush was Mardi Gras Queen.

Strings of twinkling Christmas lights hung from the ceiling between the stars he'd helped to cut out from silver paper. Waiting for the ceremony to begin, he watched the floats come in one by one. The last was a pirate ship.

"There was a treasure chest on the float," my dad recalled. "All of the sudden, it burst open and ten, maybe 15 cats jumped out, running all over the place, under the tables, under the sisters' skirts. Everybody went nuts. I was wearing a fancy Louis XIV-style costume. I didn't want it to get clawed up, so I stayed on the stage. Afterwards, things got kind of rowdy. There was a lot of drinking. But that's just what it was like on Mardi Gras."

At my dad's exit interview, his counselor advised him to keep Carville a secret so he could avoid the stigma it carried and focus on his life ahead. And he did. Unlike some former Hansen's patients who didn't want to live on the "outside," my dad chose to leave Carville when he was cured, but Carville never left him or our family. Back in New York, he served in the AmeriCorps VISTA program before becoming a social worker, a printer, and a lab technician in the Art Department at NYC Technical College. In his spare time, he was a Boy Scout leader and remained politically active, marching for Civil Rights and against the Vietnam War. In 1967, he married my mother, and opened an art supply store with her in 1972. In 1976, I was born.

Without Carville, my dad wouldn't be the man he is. And I wouldn't be who I am either. When my dad was discharged, he went home alone, just as he'd arrived. But when he returned, it was with us, the family he made, the proof that while he was gone, he didn't just survive, but lived.

King of the Armadillos by Wendy Chin Tanner (Flatiron Books/Sylvie Rosokoff)

King of the Armadillos by Wendy Chin Tanner (Flatiron Books/Sylvie Rosokoff)

Shares